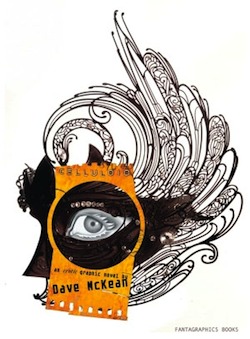

I initially learned of the existence of Dave McKean’s erotic graphic novel project, Celluloid, because Neil Gaiman tweeted about it for nearly a week straight some while back, and I figured what the hell—that sounds really interesting. McKean is a fabulous, fantastical, thought-provoking artist, whether he’s doing the covers for Sandman or children’s books; seeing what he had to say visually/narratively about sex and sexual art seemed intriguing.

So I did what most of us do when curious about something we’ve seen mentioned on Twitter: I whisked into the Google-mines to find out what people were saying about the book before I decided whether or not to pick it up. The first thing I came across—and the thing that decided me on the purchase—was an interview in which McKean discussed what it was, exactly, that he was doing with a project that was both a “dirty comic book” and a surrealist art-journey. Which also gives me, looking back on it now, an inroad past my initial roadblock in reviewing Celluloid: what the hell do I talk about when reviewing an erotic comic?

McKean says, when asked “why erotica?”:

“The depressing majority of comics seem to be about violence of one sort or another, […] And I just don’t enjoy violence. I can see that narratively it is often a powerful spike in a story, but I certainly don’t want to dwell on it. I don’t want it in my real life, I don’t find violence entertaining in and of itself, or exciting, or funny.

But sex is happily part of most people’s lives, and crosses the mind most days, I would say, even if it’s just watching your partner get out of bed in the morning. […] Most pornography is pretty awful. I mean, it does the job at the most utilitarian level, but it rarely excites other areas of the mind, or the eye. It’s repetitive, bland and often a bit silly. I was interested in trying to do something that has an aesthetic beauty to it if possible, and something that tickles the intellect as well as the more basic areas of the mind. Maybe that’s not possible, and as soon as you start to think too much, it stops working as pornography. I don’t think so, but I guess it’s in the eye and mind of the viewer.”

The quote is from the aformentioned interview about the process, motivation, and ideas behind Celluloid, over at Comic Book Resources. The thoughts McKean expresses about erotica, the nature of pornography, and the balance between the cerebral, high-art aspects of Celluloid and the titillating, sexual focus of the story had me hooked. Plus, I think he’s right—there’s still a strange puritanical recalcitrance to depict and talk about sexuality hovering in the hive-mind, while the same culture happily wallows in violence without qualm.

And that leads us to the actual comic: Celluloid, a visually told, textless story about a woman who enters the world of an erotic film she finds on a projector while waiting for her lover to meet her for a retreat together (or so I gather from the introductory panels). As for the “what the hell do I talk about” question, I suspect the answer must be what I would talk about with any other comic: the story, the art, the action, the effect. It’s just a little weirder to do this time.

There are four “chapters;” McKean’s art style shifts between each. The initially sketchy, tan-toned art when the woman enters the film-world and acts as a voyeur is balanced against photographs intended to represent the film that’s playing: shots of a woman’s mouth, her nipples, et cetera. The protagonist wanders curiously about the world here first, drawn unashamed and comfortable in her quite public nudity, and finally encounters another projector and the multiplicity of hands that come from its film to pleasure her.

Then, through to the next world—which is a surrealist, dreamy encounter with a woman who has multiple breasts. The encounter is filled with ripe fruit imagery and photographic stills of fruit superimposed over the closely drawn women’s explorations of each others’ bodies. It was at this point in the text that I let go of some of my initial reservations, because let’s be frank, men drawing women as vehicles for their own exhibitionism/voyeurism is not a new thing, and it’s usually sleazy at best and intensely irritating at worst, at least for this reader. The woman’s scene with her fantasy woman is drawn and imagined in a particular way that does strike me as authentically homoerotic—not the “girl on girl” junk you see everywhere, but a well-thought set of scenes with women enjoying each other.

The fruit imagery is artistically pretty interesting, too: the slices of fruit are photographed on top of the sketches and are designed to match the image in the drawing in shape or detail. The effect is startling, a mixture of photorealism with sketchy, but still graphically detailed, women’s bodies in the drawings. The art in this case does seem to take the mind away from the sexual content and redirect it to an appreciation of the technique and the way the pages look laid out, but it also recalls taste-smell-physical memory via the ripe fruits that then overlay the visuals of the sexual art.

And let me be clear: this is a beautiful book of art, whatever else it may also be. McKean’s work is in top form. Readers who might have shied away thanks to the age-warning or the word “erotic” would be well served to pick it up anyway and appreciate the art and the narrative he manages to make using only art. I’m not saying to look past the sex in a sex story, but—it’s certainly more than the mechanical and bland pornography he complains about in the interview.

The third section is illustrated entirely in black, white, and red, and involves the woman and a bright red “devil” figure—it’s a visually striking combination of colors, poses, and shots; it’s also the most sexually explicit section of the comic. It then leads into a surrealist orgy of men pleasuring women, including the protagonist, that reminds me of Picasso, whom McKean cites as an inspiration for this book elsewhere. Finally the woman finds another projector, and this leads into the collage-world.

The collage-world is the best part of the book, and the wildest; it is the art style Dave McKean is best known for from his Sandman covers, turned to exploring sexual fantasy and desire, the focus on the woman’s body while the man she is with is rendered only in outlines. Then she wakes as a real woman in photographic shots with a masked audience clapping for her performance, whereupon she returns to her world. The comic ends with the lover arriving to meet her and seeing the projector, then turning it on.

That ending made me wish that McKean had chosen to use or even include a male protagonist in the story—it would have been a step further outside the common boundaries of male-produced erotica, certainly, which generally depicts straight men’s fantasies while avoiding the mention of a real man at all. Men’s bodies don’t get attention in comics, generally, and they still don’t here. That is my ultimate complaint with Celluloid. In the end, though it is provocative, beautiful, and thoughtful, it still treads close to the problematic usual: using women because men are somehow not acceptable erotic subjects. The hint is there that the male lover will explore his own fantasies in the projector-world, and I would have liked to see that handled with care, detail, and artistic flair, too But ultimately, we have seen a man’s fantasies; they’ve just been given to us through a story about a woman.

In that it reads, finally, as an erotic graphic novel by and mostly for heterosexual men—a man’s fantasy about a woman’s sexual life, drawn as a woman’s authentic narrative. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that in and of itself, but it does leave me wishing for a more daring and willingness to push accepted boundaries. The art does—the focus and storyline don’t. Recalling another well-known erotic comic, Alan Moore’s Lost Girls, I am reminded of its inclusion of queer male desire and believable women’s fantasies about other women, men alone, and men together.

Still, despite my complaint, I will say that McKean does better than most in several ways though he doesn’t push this “women only” boundary; for example, he draws women as whole bodies much more often than as isolated, “detachable” parts in the way most erotica does, rendering them physically as real, whole people. I appreciated that. There is also the authentically homoerotic queer scene in his favor.

Truly, it’s tough to evaluate a book like Celluloid. The ways in which we talk about, depict, and mediate sexual desire are flitting all over the place in my reading of the text—including and especially a hell of a lot of feminist commentary on pornography. In the end I will say that I find it a worthwhile purchase for the amazing art, and because the boundaries it is trying to push—allowing artists to depict sex visually, graphically, and honestly, as much as they do violence—are well challenged. Celluloid is a hell of a project, and a brave one to have put out there for a well-known artist like Dave McKean.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic and occasional editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.